Anne Enright (photo credit: Hugh Chaloner)

By Daniel Ford

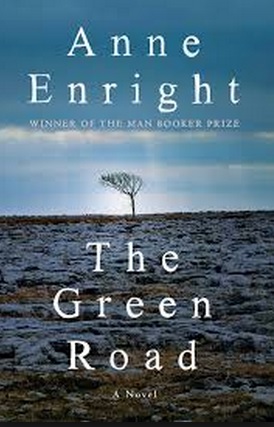

Anne Enright, author of The Gathering, The Forgotten Waltz, and, most recently, The Green Road graciously took time away from promoting her new novel to answer my questions about her early influences, her writing process, and what it means to be the first Laureate for Irish Fiction.

Daniel Ford: Did you grow up wanting to be a writer, or was it a desire that built up over time?

Anne Enright: I am beginning to think that “writer” is a word like “woman” or “heterosexual” or even ‘Irish.” We think of it as some essential characteristic, when “being a writer” is just a question of typing. A writer is someone who puts words on a page and then turns those pages into a book and then publishes that book. I could spend half my day “being” a gardener, but no one would notice, much (I spend at least five minutes a day “being” a mother). I write all day. I work. I mean I work on my sentences; how they move and what they mean. I find writing things like this interview quite painful, because the prose is so provisional, the insights too easy. But I am not sure I spend much time “being” a writer.

I used to write at school, and then I wrote out of school, a bit, and then I kept writing whether any one wanted to read the stuff or not. And then they did want to read it. The last few months are the first in maybe 30 years when I haven’t been working on a piece of fiction. It feels okay.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

AE: The houses of poets were pointed out to me when I was a girl. At least two respected poets lived near us in Dublin—one wrote in Irish, the other in English, Máirtín Ó Díreáin and Austin Clarke. Kitty, the woman who came to “do” for my mother on a Friday, used to walk up and down the hall imitating W.B. Yeats on his walk around St Stephens Green. Writers were known, respected, slightly transgressive figures in my childhood. Meanwhile, I read everything I could lay my hands on, from the age of four to, maybe 28. When I started writing I read less, but for those two decades I read maybe a book a day. Maybe.

DF: What is your writing process like? Has it changed at all since you first started writing?

AE: I work all the time. I have always worked all the time. I am slightly more productive after 30 years, but not much more productive. Every time I start a book I face the same wall I faced the last time out. I spend a lot of time looking at the wall.

DF: You haven’t tied yourself down to any one genre in your career, writing everything from short stories to essays. Is that a reflection of your personality or were you just following where your stories led? And do you have a particular favorite genre?

AE: I wrote non-fiction in order to fund my fiction writing and to maintain a profile in the three or four years between publications, so it started as a practical thing, but I came to enjoy working a non-fiction voice. I don’t like feeling stuck. I used to keep a number of things on the go so, if I hit an impasse, I would switch and work on something else for a day or two. By the time I came back, many of the apparent problems would have solved themselves. They say a change is as good as a rest, and this works for me. Changing formats is my idea of a rest.

DF: Your novels have explored a mix of family, sex, relationships, and Ireland’s past and present, and that trend continues in our most recent novel, The Green Road. What is it about those themes that keep inspiring material for you, and what were some of the other themes you explore in this novel?

AE: Actually, I don’t think I am writing about Ireland, sex, family, I think of myself as writing about some more fundamental problem like “compassion.” This was my chief concern while writing The Green Road. Ireland, and the rest of it, is just the stuff I have at hand. It is in my life, it is all around me. People said The Gathering was about family but it was about history, memory, and imagination. The reader psychologizes all the time, the critic historicizes. I think my problems are more...philosophical. I mean there is some question I have to figure out, so I sit down and write a book so as to see what the question might be. That problem is not “Ireland.” It is not “sex” or “family.” The problem is bigger, more vague: like, “How do we live?” “Who are we when we are alone?”

DF: Where did the idea for The Green Road originate, and how long did it take you to finish it?

AE: I started writing in June 2012 and “finished” in, say, September 2014. It is hard to say when a book is finished there is so much small work on galleys and proofs—this went on until December 2014—and besides the book isn’t ever finished so much as “published.”

As to where the idea came from, can I quote the poet Michael Longley by saying: “If I knew where I ideas came from, I would go back and get some more.”

DF: The book revolves the Madigan family’s matriarch, Rosaleen, who watches her children grew up and struggle in a variety of different ways throughout the narrative. Where did Rosaleen and her brood come from in your imagination, and how much of yourself ended up in each character?

AE: These are great mysteries. I see aspects of myself in each of Rosaleen’s children, and I see myself in Rosaleen towards the end of the book, perhaps, when she is a small figure in the landscape. I mean, I wrote the book, so in a way it is all me, and not me at all.

DF: In January 2015, you were named the inaugural Laureate for Irish Fiction. Congrats! What does the position entail, and what has it meant to you personally?

AE: It is a great honor, and has meant a great deal to me personally. For three years I will represent Irish fiction. I will give some lectures, curate some events. I will also teach in University College Dublin and, in the spring of 2016, at New York University.

DF: What advice would you give aspiring authors?

AE: Forget prizes. Ignore the world, engage the world. Do not become an object to other people; your book is a shifting, living manifestation of the subjective self. It happens not for the crowd but for one reader at a time. It happens not in the room but in the reader’s head.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

AE: I like gardening.