Match Made in Manhattan: 9 Questions With Playing With Matches Author Hannah Orenstein

10 Questions With The Book of M Author Peng Shepherd

Pushing Past the Stigma of Sex Toys With Hallie Lieberman

Meet Dagger Imprint’s New Editor Chantelle Aimée Osman

Silver Girl Author Leslie Pietrzyk on Sparking Literary Bonfires

Writing the Story With Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium Author A.M. Wheeler

By Sean Tuohy

Combining teenage angst with the ability to talk to a dead author, A.M. Wheeler’s Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium is a wildly entertaining novel.

The hardworking author and screenwriter swung by Writer’s Bone to talk about her writing process, who she based her teenage medium off of, and what’s next for her.

Sean Tuohy: When did you know you wanted to be a storyteller?

A.M. Wheeler: I started telling stories to my family around the dinner table when I was about 3 years old. I just have always been fascinated with stories and making up characters or scenarios that would make people laugh. So, I’d say around middle school, I kind of knew I wanted to work as a writer and possibly even direct film one day.

ST: What is your writing process? Do outline?

AW: My writing process is interesting. I don’t write everyday. I actually like to take some months off and experience different events, people, cultures, and then after think about my next story. I find allowing my thoughts to manifest for a while, makes my stories feel unforced and it’s my way of avoiding writer’s block.

I always outline! Before I begin writing a story, I always know the ending of the story before I even know how it begins! I find this technique best for me because if I know where a character ends up, I can then feel like a detective as I write backwards and leave little foreshadowing moments on how the characters ended up where they did.

ST: Where did the idea for Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium come from?

AW: Growing up I’ve always been interested in the supernatural world and the ultimate question of what happens after one dies. I knew I wanted to have a teen protagonist because high school was such a pivotal moment in my life. High school can be such a rough transition and once I knew I wanted to combine the world of high school with a supernatural twist, Zebulon Harris: Teen Medium, was born! I always find coming of age stories to be timeless and the ultimate of message really is universal to everyone.

ST: Zebulon “Zeb” Harris is a great main character. Unlike most characters he rejects his special abilities and sees them as a burden. Where did he come from?

AW: I think most teens in high school reject their situation or identity at one point or another. You know, if you’re tall you wish you were short; if you have curly hair, you wish it were straight. The concept of wanting what you can’t have is a struggle I really related to in high school. So, once I knew I wanted to write about the supernatural world and was trying to create this relatable protagonist, Zeb, I realized making him reject who he is would be what can connect teens to this book. You don’t have to have powers to understand Zeb’s struggle. I think readers can appreciate the concept of trying to discover yourself and accept yourself for who you are.

ST: Is there any of you in Zeb?

AW: I think Zeb is a lot cooler than myself! However, definitely his closeness to his family is something I think is similar to own life. I also think his sometimes sarcastic nature was exactly how I was in high school. He tended to not really care about school that much, and for a while I was the same way! It wasn’t until my junior year of high school that I started taking school more seriously. Otherwise, Zeb is actually more like my best friend from high school. A lot of Zeb’s mannerisms mimic his, and I think that’s why Zeb feels authentic. He’s actually partially based on a real person.

ST: What's next for you?

AW: I currently teach screenwriting and creative writing courses at a university. I have taken some time off from writing. However, I do have a few ideas for some scripts in the future, and I definitely think I’ll get back into the film festival scene starting after the 2018 New Year. I’m hoping to eventually get involved in some film shorts and possibly even end up behind the camera.

ST: What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

AW: The best advice I can give other writers is to stop overthinking before you write. Just write the story. It’s okay if the plot has inconsistencies, or the story doesn’t make total sense when you reread it. Editing will always be there, and rewriting. But, you can’t do anything if you stop yourself from getting anything on the page. Lastly, don’t take criticism personally. You may hear “no” way more times than you hear “yes," but don’t stop writing. Your writing can make a difference.

ST: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

AW: One random fact about me would be that when I get to a part of a story where the character is going through an extreme emotion of anger, or being in love, or sad, I listen to music that correlates that emotional state. Music helps relax my mind and makes me feel what the character may be going through. So, usually I’ll have my headphones on and I just allow the music to make me feel certain emotions before I begin writing. I find this is the closest way to be as authentic in the moment as possible, especially when writing a piece from a first person narrative.

To learn more about A.M. Wheeler, follow her on Twitter @amwheeler90.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

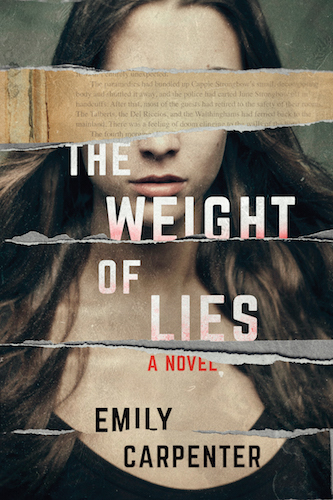

Worth the Weight: 11 Questions With Author Emily Carpenter

Emily Carpenter

By Lindsey Wojcik

The heat is on. By now, most of the country has experienced the familiar stickiness that comes with the summer season. The humidity has undoubtedly driven many to the beach or pool to cool off, and here at Writer’s Bone, no beach bag is complete without a sizzling new novel.

Emily Carpenter’s The Weight of Lies has all the makings of a classic beach companion. Vulture highlighted it as “an early entry in the beach-thriller sweepstakes.”

In her new book, Carpenter transports readers from New York City to a small, humid island off the coast of Georgia where Megan Ashley, the daughter of an acclaimed novelist, travels to discover more about her mother’s famous book, Kitten, for a tell-all memoir she has agreed to write. Kitten tells the tale of an island murder that fans believe may have been loosely based on a real crime. As the truth about where Megan’s mother, Frances Ashley, found the story for her infamous novel unravels, Megan must decide what is real and what is fiction.

Carpenter recently spent some time answering questions about transitioning from a career in television to writing novels, what inspired The Weight of Lies, and why it’s important for writers to appreciate their “customers.”

Lindsey Wojcik: You've been writing since a young age. What are your earliest memories with writing? What enticed you about storytelling?

Emily Carpenter: I’ve told this story a few times—the one about how I plagiarized The Pokey Little Puppy when I was 5. It’s my secret shame. I basically copied it word for word and illustrated it with crayons. I am not sure I actually finished it, so maybe I’m off the hook? After that, there were a couple of false starts on a novel about a girl with a horse when I was around 14. I’m not sure I had a handle on a coherent story, but I was definitely enamored by the idea of a girl (me) owning a horse. I absolutely lived for reading. I was an introvert, bookworm, a dreamer, and really imaginative. And while I didn’t really have a reference point for becoming an author, I was drawn to the whole world of storytelling.

LW: Who were your early influences and who continues to influence you?

EC: I read all of the Nancy Drew books, The Bobbsey Twins, The Hardy Boys multiple times over. Beverly Cleary and Laura Ingalls Wilder were early favorites. I loved those biography books with the orange covers, and there was another series where I remember reading about Madame Curie and Helen Keller. I read a lot of suspense books now because that’s the genre I write, but I enjoy all kinds of fiction. I’ve gone through periods when I read YA and literary classics, romance and horror. I’m really inspired by television writers right now. Noah Hawley, who writes “Fargo,” is immensely brilliant and funny. I also admire Ray McKinnon, a fellow Georgian, who wrote “Rectify.” Both those guys really inspire me.

LW: Tell us a little bit about your experience at CBS television’s Daytime Drama division. What did you do in that department? How did it influence your writing?

EC: I was the assistant to the director of daytime drama, so I basically answered phones, did paperwork, that kind of thing. I also read all the scripts for upcoming shows and wrote summaries for the newspapers to publish. I got to take contest winners on tours of the productions and assist with a couple of promo tapings of commercials for the shows. Once I took a bunch of contest winners and some of the actors to lunch because my boss couldn’t do it. I had the company credit card and had to pay for the whole thing, and it made me really nervous. I was, like 24, or something, and I’d never seen a check for a meal that big. In terms of influencing my writing, I think I really soaked up the concept of how to write tension and cliffhangers. “Guiding Light” and “As the World Turns” had some really talented writers on staff who were great at writing really funny, snappy banter, and I picked up on that—the rhythm of dialogue is so important and they were such masters at it.

I remember something my boss told me once when the writers had brought in a secondary character who was a part of this new storyline. So one Friday at the end of the show, they ended the final scene with a close up on his face. She got so mad about it and said, “You don’t end a really important scene—especially a Friday cliffhanger scene—on a day player!” She understood that, bottom line, the audience cared most about the core characters of the show. They loved them, not this random guy they’d brought in to be a temporary part of this new storyline. She knew that the show needed to leave the audience anticipating, thinking about those core characters all weekend long until Monday rolled around—not this day player. That really stuck with me, how important it was to understand who your audience was and what they wanted and giving it to them.

LW: You assisted on the production of “As the World Turns” and “Guiding Light.” Both of those soaps were on daily in my household growing up—three generations of women in my family, including myself, watched both shows, which are no longer on the air, and soap operas in general have been on the decline. What do you think influenced the change in daytime television?

EC: First of all, let me say, thank you for watching. I have a deep admiration and enduring fondness for those two shows. I watched them long after I left New York and moved back down South, and when they were cancelled, I cried. It really was such an end to an era. Although I’m sure there is an answer for why daytime TV changed, I’m not sure I know. I think, in the end, it’s probably to do with money, like everything else. And new technology and our capability to access streaming shows and binge watch really high quality programming. There’s no more appointment TV. We really have gotten out of the habit of showing up at a certain time to watch a show. I suppose the decline started with cable and cheap reality programming and TiVo. But I’m not sure what the deathblow was. And look, we still have four soaps running. I turned on “Days of Our Lives” the other day, and Patch and Kayla have not aged a whit since I watched them in the late ’80s.

LW: Tell us a little bit about your experience with screenwriting. What influenced your decision to change career paths from film production and screenwriting to writing novels?

EC: I was pretty naïve, hoping to break into the screenwriting business with zero entertainment connections or really any knowledge of the business at all. I think I had a good sense of story and structure in a general sense—I had some raw materials—but in terms of writing a kickass commercial feature, I wasn’t there. I didn’t know how to do it. And I think I was really sort of just learning the technique of writing as well. Learning how to write good sentences and evoking emotion with my words. I hadn’t majored in creative writing in school or even taken a single writing course in my life, I was just winging it. So really, it was audacious of me (or plain, old ignorant) to think I was going to write a spec screenplay that would sell to Hollywood.

But I just loved movies so much and writing and kept plugging away at it. I worked really hard and placed in a few contests, but ultimately couldn’t get an agent interested. After working on two indie productions with friends, I finally decided it was not going to happen. I took a break for a few years and hung out with my kids, enjoyed being a mom. Then one day, it suddenly occurred to me that there was this whole world of storytelling that I had overlooked. I started mulling over the idea of writing a book and researching the business side of publishing. It turned out to be much more accessible world. And I’ll say that my screenwriting experience, self-taught though it was, has formed the basis of my novel writing. I use a lot of the outlining and scene structuring tools that screenwriters use in my books.

LW: How did the Atlanta Writers Club guide you as a writer?

EC: They provided amazing access to a whole community of local writers, some of whom have become critique partners and dear friends. I found a critique group through them, which was where I read something I’d written out loud for the first time. And I attended several conferences the club sponsored and pitched my books to agents. I actually met my agent at one of the conferences.

LW: What inspired The Weight of Lies?

EC: I love classic horror books and films—Stephen King is just the master, of course. Carrie is one of my all-time favorites. One time I read that he had based aspects of Carrie on this girl he knew in school who was awkward and bullied by the other kids. That fascinated me, and I wondered if she ever found out what he did, what she would think of it. I mean, can you imagine? I get asked that question a lot, as an author, is my book based on real events or real characters? My books aren’t, but it intrigued me to imagine a writer who had the audacity to base her novel on a real murder and maybe even a real murderer, and so now there’s this eternal question out there among her fans about whether it was real.

LW: When you were writing The Weight of Lies, was there something in particular you were trying to connect with or find?

EC: Well, at the heart of the book, it’s really a story of this young woman who doesn’t feel like her mother has ever loved her or really even wanted her. And she’s so angry because she’s desperate to be affirmed and loved. She’s also a bit lost because she doesn’t have a whole lot going on career-wise, she hasn’t really been successful in the romantic department, and she’s getting older. She’s got a lot of resentment toward her mother to work through, but she’s really blinded by her pain. And her mother really is a monumentally self-centered diva, so there’s plenty of blame on both sides. That whole situation felt really compelling to me, that search to try to understand your mother as more than just the figure you rebelled against or had conflict with. Where you reach a crossroads at which point you have to decide whether you’re going to give your mother the benefit of the doubt and forgive her, or feed your childhood bitterness and hurt and go for the scorched earth option. Needless to say, Meg opts for earth scorching.

LW: How was the process of writing The Weight of Lies different from writing your debut Burying the Honeysuckle Girls?

EC: With Honeysuckle Girls, I had a lot of time. A lot of freedom. I was 100 percent on my own timetable. Then, once I signed with my agent and went on submission, it became a process of listening to my agent’s opinions and the opinions of the marketplace and deciding what to pay attention to and what to bypass. The great thing was that I had a lot of time to tinker with the book, which is a luxury. It wasn’t that much different writing The Weight of Lies because I didn’t sell the book until I had completed it. My next books, though, were sold on pitch, so that’s been an entirely new process, to deliver something you’ve already been paid for.

LW: What’s next for you?

EC: I’m writing my next book, which is about a young woman with a secret she’s kept since her childhood, who agrees to accompany her husband to an exclusive couples therapy retreat up in the mountains of north Georgia so he can get help for the nightmares that have been plaguing him. And then things start to go sideways, and she realizes that nothing at this isolated place is as it seems.

LW: What’s best advice you’ve ever received and what’s your advice for up-and-coming writers?

EC: My agent told me once, “Remember, this is your career…” I can’t even recall what we were talking about exactly—it might’ve been a deadline, or what I was going to write next—but the point was, she wanted me to clear away all the noise from other people’s expectations and do what was best for me. To follow my heart. It was just what I needed to hear at the moment, especially because I have the tendency to go overboard to make other people happy and overlook what’s in my own heart. It really settled me down and gave me the confidence to go forward.

I think one of the things I’d like to remind up-and-coming writers is that they are getting into a business and many of the decisions that editors and publishers make have to do with money. So when new writers encounter perplexing situations, I think they need to understand that financial bottom line motivates many of them. It’s sometimes a bitter pill to swallow, but it’s reality. And as writers, we have to be able to nurture our art in that atmosphere of commercialism.

The other day I heard Harrison Ford say in an interview that he doesn’t like to call people who see his movies “fans,” but “customers.” It was a really pragmatic, non-romantic way for an actor or artist to view what they do, but it did sort of speak to me because I tend to lean toward being really practical. I do see the artistic side of writing, and I can get really swept up in the magic of creating characters and a story. On the flip side, I also do really appreciate my “customers,” and I consider it an honor to have the opportunity to entertain them. And I think what the customers wants and expects should matter to writers. It’s not the end-all, be-all, but it is something to keep in mind.

To learn more about Emily Carpenter, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @EmilyDCarpenter.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Giving Back to the Universe: 8 Questions With Fantasy Author Mackenzie Flohr

Surprise and Discovery: 10 Questions With Spaceman of Bohemia Author Jaroslav Kalfar

Literary Agent Sharon Pelletier Explains How Research and Twitter Can Advance A Writer’s Career

Sharon Pelletier

By Lindsey Wojcik

Literary agent Sharon Pelletier loves Twitter.

I know this because I’ve followed her for years and have always appreciated her witty take on "The Bachelor," plus our shared obsession with wine, and love and appreciation for Justin Timberlake. She also happens to hail from my home state of Michigan.

While I appreciate following her commentary on our shared interests, I also find her tweets offer important information for writers looking to land a literary agent or anyone seeking information on the publishing industry in general. Pelletier currently works as a literary agent at Dystel & Goderich Literary Management in New York City. She counts Amy Gentry, author of Good as Gone, which The New York Times recommend as one the best nine thrillers to read this summer, as a client.

Recently, I noticed Pelletier tweeting with the Manuscript Wish List hashtag (#MSWL), which inspired me to dig deeper and find out more on her manuscript wish list, what she looks for in query letters, and her advice to aspiring writers.

Lindsey Wojcik: How did you get your start in publishing?

Sharon Pelletier: I moved to New York City at the ripe old age of 25 and applied ceaselessly to every publishing job I could reasonably fit my resume into until I got an internship at a small press. Then I went to every mixer, event, and happy hour I could to meet people, collect business cards, and hustle up interviews—all while working 40 hours a week at Barnes & Noble and freelancing like crazy, mind you! It was a very exciting, exhausting, and skinny time in my life. Eventually my internship led me to a full-time position as an editor at another small publishing company, and I was off to the races.

LW: You've worked in many facets of the industry, from bookstores to a small press to a self-publishing company and now at an agency. How have those experiences shaped your role as agent?

SP: I’m glad I made a few stops on the way to being an agent because I have a full understanding of the whole publishing process! I’ve worked in editorial, production, and marketing, in addition to my time as a bookseller, which has made me better able to answer clients’ questions, evaluate publishers, or offer suggestions if a book needs to be jumpstarted. Of all of these jobs, being a bookseller might be the most useful, in a way, because I learned how different readers make buying decisions, from the hardcore readers who go through 50-plus books a year to genre devotees to folks who pick up one or two books a year from the nonfiction categories. Learning the reading tastes of customers who came in regularly for recommendations was good practice for profiling an editor’s taste.

LW: What steps do you recommend an author take when trying to land an agent?

SP: Step one: research! You’ve put a lot of time into finishing your manuscript and polishing it until it’s the best you can be, right? Writers are often eager at this point to start launching their work out there, but it’s best to put the extra time into learning how to query effectively. If you’re brand new to the process, seek out blog posts and other resources online to learn how to write a strong query letter and how to find the agents seeking your kind of manuscript.

Twitter is another great way to get to know agents’ individual preferences, both what they’re looking for their list, and their favorite television shows, pet peeves, etc. Twitter is also perfect to connect with other writers at the same step of the process for support and tips.

LW: How can writers develop a quality query letter that catches an agent’s eye?

SP: Again, research! The things we ask for like word count, genre, comp titles, show that you’ve researched your market and understand your readership—and that you know we work in that category. Writing is about art, but being an author is also about business, and as much as we’re looking for manuscripts we love, we’re also looking for authors with career potential who will be a strong partner for us. So a well-researched, carefully crafted query that follows industry standards and our specific agency guidelines shows that you’re taking the business side of writing seriously and putting the time into careful research.

There’s a lot of info online (including on the DGLM blog) about the components of a strong query letter, but here’s the short version:

- Opening: 1-2 sentences with genre, word count, comp titles, and mention of why you’re querying this agent (I follow you on Twitter, we met at X conference, I read your client X’s book and loved it, etc., for example)

- Story pitch of around 200 words. Highlight characters, world, and stakes—think about what would be on the back of your book’s cover in the bookstore.

- Bio: 2-3 sentences about who you are, including publication credits, experience you’ve had that informed this book, etc.

Rather than querying every agent whose email address you can find, put the time in to query a handful of agents who seem like the ideal fit—take the time to seek out details on their website, their #MSWL, interviews they’ve done, books they represent, etc. Then you can write a strong personal query mentioning why you’ve queried this agent in particular.

LW: What is the most common mistake you see from first-time authors?

SP: If you’re speaking of the query process, I gotta spout my favorite word again: research—or the lack thereof.

If you mean in the writing itself, one common rookie mistake is to open with your character waking up in the morning or some variation on “The day that changed her life started like any other day.” Don’t tell us that—show us! If your plot starts with a weird email when your character gets to her office, show us her sitting down at her desk with a mug of hot tea, or checking her email on the phone while sipping a smoothie on her way out of the gym. In either scenario, you’re showing us something about the character’s personality and lifestyle that is more important than us knowing what color her hair is or what she’s getting dressed in. You’re setting the character’s “normal” just before the unusual interrupts to start the story.

LW: What do you look for when you're reading a manuscript?

SP: I want to be absorbed in your story to the point that I forget I’m reading a submission and am just reading. And this usually comes down to voice, which is an easy term to throw around and harder to define or teach. It’s not about splashy, lavish descriptions or sassy dialog. Does your main character seem real and alive, like I could picture her walking around in the real world outside the page? Do her obstacles have stakes? Am I invested? Have you created a time and place for the story and drawn me into them? All of these questions matter whether you have a fast-paced crime thriller or a quiet family story set in familiar suburbs.

And the best way to develop your voice as a writer, paradoxically, is to read widely and deeply. Reading teaches your brain quietly how to pace a story, how to seed in details without drowning the reader in description or back story, so that your distinctive voice can emerge.

LW: Speaking of manuscripts, you've been active on Twitter using Manuscript Wish List's #MSWL hashtag. What's your involvement with Manuscript Wish List and what benefit does it offer agents, editors, and authors alike?

SP: Manuscript Wish List existed for a long time on Twitter as a hashtag where agents could tweet genres they’re interested in or story ideas they’re dying to represent. Sort of the reverse of a Twitter pitch event, it is the brainchild of an agent named Jessica Sinsheimer. In the last year or so, it’s taken on even more momentum with a very snazzy website where agents and editors can post profiles about what categories they represent and the kinds of stories within each category they’re most eager to see—and perhaps most handy of all, update those profiles as often as they like as their lists change. It seems to be a great help to authors in finding agents hungry for manuscripts like theirs.

And on my end, my eyes perk up when I see someone reference my MSWL in a query! It’s a nice shiny sign of an author who’s putting in the research and is plugged in to the latest in the writer community. I don’t think I’ve signed a project that way yet, but I’m sure I will soon!

LW: What's on your Manuscript Wish List?

SP: Right now I’d love to find some smart narrative nonfiction that brings that perfect combo of gripping storytelling and merciless research—something like Brain on Fire or Five Days At Memorial. I’d love to work with journalists who have a long-form book project. I’d also be interested in working with cultural voices with a growing platform—the next Lindy West or Ta-Nehisi Coates. And I think I’ll always be eager for smart, upmarket suspense (think Tana French or Gillian Flynn) and book club fiction that’s warm and earthy but not sappy—Ann Leary and Delia Ephron are two writers I’ve loved lately.

LW: What's your advice for aspiring writers?

SP: Find a community of writers to connect with! Whether it’s in your local area or online, find other writers in your category who take their writing seriously. They’ll be valuable as critique partners when you’re in the early stages of perfecting your manuscript, and more importantly, you’ll have a built-in fan club when you’re moving toward an agent and a publishing deal. There’s a lot of waiting, a lot of struggle, and a lot of disappointment along the way to a successful career with adoring readers and having support from writers who know what’s it’s like is key for boosting you during the hard patches. Finding writer friends at different stages of the process can be especially helpful for advice and encouragement! Even if your loved ones are your biggest fans, they don’t really know how it feels when you have writer’s block or have to cut out a scene you absolutely love.

LW: What is a random fact about yourself?

SP: Wow, this is the hardest question of all, I think! Hmmm, I’ll give you a few to choose from: I’m the oldest of seven, never went to school, and would choose mashed potatoes over pie any day of the week.

To learn more about Sharon Pelletier, follow her on Twitter @sharongracepjs.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Imagination On Fire: 10 Questions With Author Joe R. Lansdale

Joe R. Lansdale

By Sean Tuohy

Joe R. Lansdale is a writer’s kind of writer. I don’t think there’s a storytelling medium he hasn’t worked in. He’s penned 30 novels, most of them taking place in his home state of Texas. He’s also worked on comic books, television shows, films, and newspapers.

Lansdale’s stories are filled with strange, yet relatable characters. His stories are original and fast- paced. Lansdale grabs his readers quickly and pulls them into a world created by a master storyteller.

Recently his novel Cold In July (a personal favorite we featured in “Books That Should Be On Your Radar” in March) was produced into an award-winning film starring Don Johnson, Michael C. Hall, and Sam Shepard. His long-running Hap and Leonard series has also been turned into a TV series.

Lansdale took a few minutes to chat about the craft of storytelling, how he works in so many different mediums, and his new publishing house Pandi Press.

Sean Tuohy: When did you decide you wanted to become a storyteller?

Joe R. Lansdale: I was four when I discovered comics. I wanted to write and draw them. By the time I was nine, I realized I liked writing, but didn't really have the talent to draw. Stories, novels, and TV shows, movies influenced me as well. So pretty much all my life.

ST: Who were some of your early influences?

JRL: Jack London, Twain, Rudyard Kipling, and Edgar Rice Burroughs are a few. Burroughs really set my youthful imagination on fire. I wanted to be a writer early on, but when I read him at eleven years old, I had to be.

ST: What is your writing process like?

JRL: I get up in the morning, have coffee and a light breakfast and go to work for about three hours. That's it. I do that five to seven days a week. Now and again I'll work in the afternoon at night, but that's mostly how I do it day in and day out. I polish as I go and try to get three to five pages a day, but sometimes write a lot more.

ST: You have written for TV, film, and comics. Does your process or writing style change between the three formats?

JRL: Well, the format is the change, but you always write as well as you can, and you write to the strengths of the medium. Each as different, but you try and do them all as well as you can. I find I sometimes need a day to get comfortable doing something other than prose, but then the method comes back to me, and I'm into it.

ST: Your novel Cold in July was turned into a film and your long running Hap and Leonard series was turned into a TV show. How does it feel to see your work translated into another form?

JRL: It's fun, but always a little nerve-wracking. You always see stuff they left out, or changed, but my experiences so far have been really good. Enough things get made, I'm sure to have one I really hate. But again, so far, way good.

ST: Recently you opened Pandi Press with your daughter Kasey (a talented singer). What is the goal of this new publishing house?

JRL: To publish some of my work that's out of print, and to make the money that the publisher would end up with if they reprinted. It's an experiment as well. We'll see how it turns out. I plan to do some original books there as well.

ST: Being from Texas the Lone Star State plays a big part in your stories. What is it about Texas that makes it such an interesting backdrop filled with interesting characters?

JRL: You said it. It's full of interesting characters. But the main reason is it's what I know well, and I can write about it with confidence.

ST: What is next for Joe Lansdale?

JRL: More novels, short stories, films, and comic adaptations of my work by others.

ST: What advice do you give to first-time writers?

JRL: Read a lot, and put your ass in a chair and write. Only two things that really work.

ST: Can you tell us one random fact about yourself?

JRL: I have been studying martial arts for 54 years.

To learn more about Joe R. Lansdale, visit his official website, like his Facebook page, or follow him on Twitter @joelansdale.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

A Conversation With Brash Books Co-Founder Lee Goldberg

By Sean Tuohy

Heart-pounding. Eye-popping. Jaw-dropping. These are all adjectives you could use to describe the titles published by Brash Books.

Lee Goldberg—a television writer, producer, and author of several best-selling novels—and former trial attorney-turned-successful author Joel Goldman, formed the company. The two "golden boys" bring thrilling novels to the public by managing a stable of exceptional writers that never disappoint.

Goldberg was kind enough to take a few moments to chat about Brash Books, the world of publishing, and what he looks for in a manuscript.

Lee Goldberg (right) and Joel Goldman

Sean Tuohy: What books did you read growing up?

Lee Goldberg: Mostly mysteries and thrillers. I was weaned on The Hardy Boys, Encyclopedia Brown, The Three Investigators, etc. I then moved on to The Saint (Leslie Charteris), Matt Helm (Donald Hamilton), Travis McGee (John D. MacDonald), Fletch (Gregory MacDonald), James Bond (Ian Fleming), Lew Archer (Ross MacDonald), as well as devouring literary novels and westerns. I began reading at a very early age and would read three or four books a week for pleasure. It was also my education, but I didn’t realize that at the time. My favorite authors, besides those I previously mentioned, were Leon Uris, Robert Ludlum, Stephen King, Arthur C. Clark, Graham Masterton, Richard S. Prather, Clive Cussler, Sidney Sheldon, Ray Bradbury, William O. Steele, Arthur Hailey, John Irving, Lawrence Sanders, Larry McMurtry, Lawrence Block, and Elmore Leonard. I could go on and on and on.

ST: What lead to the creation of Brash Books?

LG: All mystery writers have them—the cherished, often under-appreciated, out-of-print books that we loved and that shaped us as writers. They are the books that made an impression on me in my teenage and college years and still feel new and vital to me today. They are the books that I talk about to friends, thrust into the hands of aspiring writers, and that I wish I’d written. They are the yellowed, forgotten paperbacks I keep buying out of pure devotion whenever I see them in used bookstore, even though I have more copies than I’ll ever need.

I’ve been at this long enough that many of my own books have fallen out-of-print, too. But I brought them back in new, self-published Kindle and paperback editions and, to my surprise and delight, they sold extremely well. It occurred to me that if I could do it for my books, why couldn’t I do the same thing for all those forgotten books that I love?

So, a little over two years ago, I started negotiating with the estate of an author whose books I greatly admire but that never achieved the wide readership and acclaim that they deserved. I was in the midst of those talks when, at a Bouchercon in Albany, I told my buddy Joel Goldman, a good friend, mystery writer, lawyer, and a successful self-publisher of his own backlist, what I had in mind.

Joel got this funny look on his face and said, “That’s a business model. I really think we’re really on to something.”

We?

It turned out that, like me, he’d been getting hit up constantly at the conference by author-friends who were desperate for his advice on how they could replicate his self-publishing success with their own out-of-print book, many of which had won wide acclaim and even the biggest awards in our genre. He’d been trying to think of a way he could help them out.

Now he thought he had the solution. What if we combined the two ideas? What if we republished the books that we’d loved for years as well as the truly exceptional books that only recently fell out of print?

It sounded great to me. And at that moment, without any prior intent, we became publishers of what we considered to be the best crime novels in existence. It was a brash act and that’s how, as naturally as we became publishers, we found our company name.

Brash Books.

One of the first calls I made was to Tom Kakonis, whose books were a big influence on me, to ask if we could republish his out-of-print titles. He was glad to let us take a crack at it. He also mentioned that he had a novel that he wrote some years ago, but had stuck in a drawer because he’d been so badly burned by the publishing business. I asked if I could read it and he sent it to me. I was blown away by it and so was Joel. We couldn’t believe that a book this good, that was every bit as great as his most-acclaimed work, had gone unpublished. It was a gift for us to be able to publish it. And that’s how, unintentionally, we decided to publish brand new books, too.

Tom’s unpublished novel, Treasure Coast, became our lead title when we launched in September 2014 with 30 book from authors as diverse as Barbara Neely, Dick Lochte, Gar Anthony Haywood, Dallas Murphy, Maxine O’Callaghan, Bill Crider, and Jack Lynch. In our first year, we published eight to 10 novels each quarter, one of which was a brand new, never-before-published book. In November 2015, we changed up and published only three books all brand new, never-before-published titles. That was a big success for us. So now we’re on track to publish two or three books a quarter, one or two of which are brand new, the others back-in-print titles from the back lists we've acquired.

It’s a business that’s very much a labor of love for us both. We get a bigger thrill now out of seeing new copies of our authors’ books than we do our own. The widow of one of our authors got teary-eyed over Brash’s editions of his out-of-print books because we were treating them the way he’d always wanted. We got tears in our eyes, too. We started Brash Books for moments like that and for Tom’s dedication in Treasure Coast:

“For Lee Goldberg, who may have rescued me.”

Our goal is to introduce readers, and perhaps future writers, to great books that shouldn’t be forgotten and to incredible new crime novels that we hope will be cherished in the future.

And yet, to our frustration, our list still doesn’t include any books by that obscure, deceased author who brought Joel & I together in this brash, publishing adventure. We’re still negotiating with that author’s estate. But we’re not giving up. I love those books too much to let go. I just bought two more of them at a flea market today.

ST: Was it difficult to switch from writer to publisher?

LG: Not really, because as I mentioned before, I self-published my out-of-print backlist and some new work. I also launched an original, self-published series called The Dead Man. William Rabkin and I wrote the first two books, and then we hired authors to write the others, putting out a new book each month. It was a big success. Amazon Publishing's 47North imprint picked up the series and it ran for two years. We did 24 novels with Amazon. It was great fun.

ST: What do you look for in a manuscript?

LG: What we look for is a strong voice, a fresh approach, a compelling plot, well-developed characters, and absolutely no clichés—in phrases or situations. If we aren't wowed in the first 25 pages, we know our readers won't be, either. We also look to our Brash motto—“we publish the best crime novels in existence"—as the bar each manuscript has to meet. If we can't say that we honestly believe the book lives up to that hype, we can't publish it.

ST: How do Brash Books readers influence what you publish?

LG: If readers clearly love the first book in a series, and buy a bazillion copies, that gives us an incentive to publish more. If they sales are terrible, we aren’t likely to release any sequels. That goes for both backlist and new titles, of course.

ST: As a publisher, what are the biggest issues you find with new authors?

LG: Terrible, cliché-ridden writing, and one-dimensional, stock characters.

If I read one more submission about a drug or alcohol addicted, divorced cop/FBI agent/journalist/PI haunted by the death/murder/suicide of a beloved friend/family member, misunderstood and unappreciated by his incompetent bosses, and tormented by a deranged serial killer, I might have to set myself on fire.

ST: What does the future hold for Brash Books?

LG: I hope tremendous success for our authors and their terrific books!

ST: What advice do you give to new writers? Both as a writer and publisher.

LG: If you want to write, you have to read. That’s the best education for a writer.

Proofread your manuscript.

Do not frontload your manuscript with exposition. It’s boring and it’s lazy.

Query letters are important. If your query letter is sloppy, unfocused, badly written, filled with clichés, and addressed to a literary agency or someone else besides us, the odds of us reading your manuscript have plummeted below zero.

ST: Can you tell us one random fact about yourself?

LG: I’ve just discovered, and fallen in love with, limoncello. I am going to try to make some myself.

To learn more about Brash Books, visit the company’s official website, like its Facebook page, or follow it on Twitter @BrashBooks.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archives

The Promise of Prose: 5 Questions With The Queens Bookshop

By Lindsey Wojcik

Nestled between a nail salon and a residential building on Austin Street—a shopping mecca in the heart of the Queens, N.Y., neighborhood Forest Hills—is a welcoming café that serves organic coffee, as well as vegetarian and vegan bites. Although Starbucks is nearby, the Red Pipe Café stands out on its own as a charming, much quieter shop where Forest Hills residents can gab with friends over a sandwich or take in a new book while sipping a piping hot latte.

As I entered the Red Pipe Café on a chilly February night, it became clear why Natalie Noboa, Vina Castillo, and Holly Nikodem selected the location as the meeting place to chat about The Queens Bookshop initiative. The café is less than a five-minute walk from the former space occupied by Barnes & Noble, where Noboa, Castillo, and Nikodem once worked together. The Barnes & Noble, beloved by neighborhood residents for more than 20 years, closed late last year. In an effort to fill the void caused by Barnes & Noble’s absence, the women launched the Queens Bookshop initiative with hopes to bring an independent bookstore to Forest Hills.

The Red Pipe Café served as the perfect setting to meet Noboa, Castillo, and Nikodem. Its cozy atmosphere—similar to what I imagine The Queens Bookshop’s space will offer—helped guide an effortless conversation about the trio’s goals and dreams for the bookstore they long to create. That discussion evolved into an in-depth feature about The Queens Bookshop initiative. However, some important and fun topics were left unused at the bottom of my notes. The benefits of bookselling and book recommendations are front and center in this previously cut-for-space Q&A with Noboa, Castillo, and Nikodem.

Lindsey Wojcik: What stands out to you as the most rewarding benefit of being a bookseller?

Natalie Noboa: I've worked at Borders, Books-A-Million, and Barnes & Noble, so I have a little bit of history. My absolute favorite thing was telling people what my favorite books were and having them actually buy them and come back and be like, "You were right!" I would especially do that for little kids because my favorite book as a 10-year-old was The City of Ember, which in my opinion is totally underrated. I would recommend it, they would get it, and their parents or somebody would come back and be like, "They want the rest of the series." I love that feeling. I think it's going to be easier to do that in a less corporate environment because we’ll have more freedom to go up to someone and talk about the books we love.

Vina Castillo: Yes, recommending books is one of my favorite parts of being a bookseller. But it is also refreshing when customers share their favorite reads with me, I’ll never forget when an elderly woman recommended The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. Her pitch was that her granddaughter had begged her to read it and once she did, it brought her to tears and became one of her—and thanks to her one of mine—favorite books despite it being shelved in the YA section. I could rant forever about books being dismissed because of the age range in which they are shelved.

I also really love creating my own displays. I'm looking forward to doing that again in our own store. There are so many underrated books that should be displayed and appreciated by readers.

NN: The opposite is true; there are so many books that are displayed that shouldn't necessarily be.

Holly Nikodem: Same. The most rewarding thing is when you a recommend a book—especially for me, because I worked in weird parts of the store, like comic books. Filling the shelf and listening to the people next to you talk and adding your two cents, "Oh yeah, I read that," and having them turn around and say, "Oh, you read that too?" and making instant five-minute friends over things you have in common. Maybe you'll never see them again or maybe they'll come back be like: "Oh did you find the newest issue of whatever it is?" But it was always cool to see them light up because they share something with someone.

LW: Why do you feel that bringing literacy to Queens is important?

NN: I went to school to become an English teacher so I’ve seen what kids can be like. It's crazy to me to see that they aren't that interested in reading. It's not just a school thing or about comprehension. For me, it's about getting invested in a really good book and being able to go to so many different places and go on so many different adventures without ever leaving your head. It's so sweet and so nice. And to see kids who are supposed have so much excitement about this just not care, it breaks my heart. If they don't see people excited about reading, it's out of sight, out of mind. If they don't even see a bookstore, why are they going to want to read a book?

HN: One of the counters I stumbled upon, was [doesn’t Queens] have a lot of libraries? But as a child, owning your favorite book and no matter what time, going and picking up that book, and having that comfort, is important. For an academic though, owning a book is also important. Let's say you're not very good at school and need to take your own time, owning the book is so much better than borrowing the book. It's yours. If you need to write in the book, go ahead and write in it. If it takes you longer, it takes you longer. If you have to revisit it later, fine. Later, when you grow up and find your favorite book all dog-eared, you can remember how it changed you. That's why, sure there are libraries, but the ownership of books is a completely different outlook.

LW: If your store was open today, what would be your staff pick?

HN: A Darker Shade of Magic by V.E. Schwab. It’s one of three books I've read more than once. It's just a fun little fantasy novel.

VC: Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran Foer. My first copy—yes, I own multiple editions of it—is extremely yellowed, bent, and stained because I have loaned it to anyone and everyone who has asked me to recommend them a book.

NN: Until the End of the World by Sarah Lyons Fleming. It's a zombie apocalypse series that is not as appreciated as it should be.

LW: What's a book you can't live without?

VC: The entire Harry Potter series. These books played a big part in my proud realization that I am a book lover through and through.

HN: House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. It entered my life sophomore year of college and has been present ever since in some way or another. Also one of my favorite albums stemmed directly from it. I listen to it every day.

NN: The City of Ember by Jeanne Duprau. It was one of the first books I found and purchased on my own as a kid and I fell in love with it. It introduced me to the genre I am obsessed with to this day and shaped me as a growing reader.

LW: What's a random fact about each of you?

NN: There are mixed reactions on this. Some people get very mad, some people don't care, but I have never in my life eaten a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

HN: I'm amazed.

NN: It's become a matter of principle, and now I can't. I had to have been 19 or 20 when I realized I had never eaten one.

HN: I have been stranded in the middle of the Serengeti in Tanzania twice. I volunteered two summers in a row with a school off the shores of Lake Victoria in Tanzania. Getting to the main city of Arusha to this school, twice our Jeep broke down in the Serengeti. One time we were stranded for hours and they drove us to another hotel to wait. The second time, we got stranded and it was dark. You're not allowed to drive in the Serengeti after dark, so they found us a rest house, which are basically these houses that people rent out in the Serengeti if you can't get out. We rented out the whole house and they locked us in to keep the baboons out. We got out the next morning.

VC: I have a stranded story. I was in Dublin back in 2010 when the volcano erupted. My friends and I were stranded for three nights. The planes weren't running, so we hopped from Dublin to London and took four to five trains and two boats to get home. We slept at the airport and took showers at the YMCA. It was crazy but definitely brought us closer as friends.

NN: Now my peanut butter fact seems lame! Holly has a stranded story in the Serengeti, Vina has a stranded story because of a volcano. I have a volcano story! I climbed a volcano in Ecuador.

To learn more about The Queens Bookshop, read Lindsey’s feature “The Queens Bookshop Aims to Bring Books Back to Forest Hills.” To learn more about the future bookshop, visit its official website, like its Facebook page, or follow it on Twitter @bookshopqueens.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

Author Enthusiast: 10 Questions With Literary Agent Christopher Rhodes

Christopher Rhodes

By Daniel Ford

My usual correspondence with literary agents tends to involve a lot of weeping and angst, so I’m always thrilled when an agent takes the time to patiently explain the publishing process to our readers.

I connected with Christopher Rhodes, a literary agent for The Stuart Agency, after I heaped praise on his client Taylor Brown’s Fallen Land. It was one of the rare times I gave an agent homework knowing it would result in positive answers (okay, so I slipped him my query letter and a sample chapter, I’m not an idiot)!

Rhodes’ insights into the publishing realm should give aspiring authors all the knowledge they need to sensibly chase their literary dreams.

Daniel Ford: How did you get your start in publishing?

Christopher Rhodes: I grew up in New Hampshire and I worked at a bookstore in high school and this gave me experience enough to land a job at the Borders’ flagship store in New York City at the World Trade Center.

I started working at Borders shortly after it opened in 1996 and stayed through 1999. The three-floor store was insanely busy from 12:00 to 2:00 p.m., Monday through Friday, and I loved working the cash wrap and learning what people were buying. Booksellers gain a wide knowledge of the book market just by seeing and touching books on a daily basis.

While at Borders, I took on the responsibility of maintaining a local interest book kiosk at Windows on the World, the restaurant and bar on the top floors of the North Tower. For a kid from small town New Hampshire who dreamed of living in New York City, this was pretty exciting stuff. Eventually, through friends, I met a man who did publicity for Simon & Schuster and he got me an interview for an entry level sales position there. Off I went to Rockefeller Center and a career was born. From sales I moved upstairs to marketing and worked for the inimitable Michael Selleck before getting hired by literary agent Carol Mann who taught me this side of the business.

A handful of us from that Borders have gone on to really exciting careers in publishing and many of us are still friends. Maybe you’d call it being in the right place at the right time, but I’m also the right person. I fell in love with books as a teenager and I just can’t imagine doing anything else. Publishing was lucky to find me!

DF: Since entering the publishing world, what major changes have you seen?

CR: One major change I haven’t seen since entering the publishing world is that e-books have not beaten up print books and stolen their lunch money.

I started working in the sales division of Simon & Schuster in 1999 and if you had asked me then, I would have told you that the printed book would disappear in three year’s time. There was a fear in the air surrounding the unknown technology and what it would mean to trade book publishing. Turns out the fears were justified, except it wasn’t the e-book we should have been afraid of, it was Amazon.

Lessons are still being learned but I feel like the beginnings of a silver lining have started to appear, especially evidenced in the revolution of the indie bookstore and its power to drive the market. I have two debut novels publishing in January—Taylor Brown’s Fallen Land (St. Martin’s Press) and W.B. Belcher’s Lay Your Weary Tune (Other Press)—and both of them have received enormous pre-sales support from indie bookstores, Brown’s predominately in the southeast where he lives and where the novel is set and Belcher’s predominately in the northeast where he lives and where the novel is set. This kind of specified, regional support is immeasurable and so meaningful to the success of a book. To be able to put an author in front of a bookseller, to have them shake hands and have a conversation, and then to have the bookseller tell her customers about the book, I get chills thinking about this philosophy of salesmanship. I’m very grateful to the publishers my authors are working with who understand the importance of putting a human face behind the books they are selling: St. Martin’s Press, Other Press, Tin House Books. To me, this is a throw back to old school publishing and bookselling, pre-Internet days, and I’m glad it isn’t a major change.

DF: What steps do you recommend an author take when trying to land an agent?

CR: The first step, and the one that is often overlooked by would-be authors who email me asking for representation, is the step of becoming a writer.

Over and over again, in reading submissions and queries, I notice that writers are trying to find an agent too soon in their careers, and this is true for both fiction and nonfiction writers. I would love to believe in the myth:

Unknown writer connects with big name literary agent! Seven- figure deal and film option follow!

That’s all very Lana-Turner-sipping-a-Coke-at-a-Hollywood-drug-store, but it isn’t reality. What I do as an agent is meet an author after she has put in the very hard work—writing, publishing in journals and national magazines, building a marketing platform, winning awards, being noticed for her work, or becoming an expert in her field—and navigate her through the business of trade publishing and get her the best possible deal (which doesn’t always mean the biggest advance).

As an agent, I don’t see myself as a star maker but as a star enthusiast who walks with an author on the last mile to shape her book project into something that will catch an editors eye. Then, if I’m lucky, I get to stick around to manage her career. I also get to be a confidant and business adviser to the writer, but writers make themselves a big deal by being good at what they do and by devoting time and energy to their craft. I read a lot of fiction query letters and nonfiction book proposals and the first things I look at are the author’s credentials. If you are asking me to represent you but have not proven yourself as a writer, I can’t help you.

Other important steps include writing a strong query letter (more on this below), being persistent but professional, especially if you have the credentials to back up your persistence. Remember that I am busy and that although reading query letters and submissions is a most necessary part of my job, it is also a part that I have to do on my own time. Having a roster of active clients means that book projects are always in various stages of the publishing process and active clients are given priority. When you are an active client, you will expect this to be the case. Trust me.

The final step I’ll mention here is perseverance. If you are talented, have strong credentials, have written a fantastic query letter or book proposal, and have been persistent and professional with an agent, then don’t give up. On more than one occasion I’ve seen a book project I’ve passed on that sold a few weeks later by another agent. Just because I don’t understand how to sell a certain concept or I don’t fall in love with a novel enough to go to bat for it, doesn’t mean that another agent won’t feel completely differently about it. In the mean time: see you at Schwab’s!

DF: How can writers develop a quality query letter that catches an agent’s eye?

CR: I think writers should stop trying to reinvent the wheel when it comes to query letters. There are plenty of examples of good query letters accessible via the Internet and all you have to do is pick one and mimic its format, paragraph by paragraph, but with your own original content.

Bear in mind that I read a lot of query letters and instead of this fact translating into, “he must want something fun and quirky and original with a pink font and a bunch of non sequitur information about my goldfish,” it means I value consistency above all things. I like to know that I can skip to the bottom of the query letter to glance at your credentials, or that I can bring my eyes to the first paragraph to read the brief description of the book.

My pet peeve is when writers give personal information in a query letter. I am not your therapist. A few weeks ago my college intern emailed me to say she didn’t know what do do about a query we received from a man who wrote in the first line of his letter that he was dying and that we were his last chance to have his book published. That’s a lot of pressure for a 21-year-old student getting ready for final exams! I had her forward me the email and I deleted it without reading. That might sound harsh to you, but it is impossible to be objective about the work if a writer is making it personal from the very beginning.

I can see through gimmicks and to me they are signs that in all likelihood your book project isn’t very strong. Let the work stand for itself and give me the facts.

DF: What is the most common mistake you see from first-time authors?

CR: It is hard to pick the most common, but a mistake I see over and over again from writers is that they are unwilling to have their work vetted or work-shopped by their peers. I work with a lot of debut writers, both fiction and memoir, and the best relationships I have are with those that are used to having their work critiqued. The revision process with an agent can be brutal.

Many writers get used to this process in an MFA program but an MFA is not a requirement to publishing a book. Many towns have writing groups and if not, you can start your own. Ask people (not friends and family) to read your work and be willing to listen and take feedback.

Consider this: if you send me a manuscript and I like it very much, I’m going to ask my intern Lori (who is fantastic) to read it and to weigh-in, then I’m going to ask Andrew Stuart, owner of the agency for which I work, to give me his opinion. Then, if I take on your project and we are fortunate enough to find an editor who responds to the manuscript, that editor will have to convince his fellow editors, his publisher, the sales force, the marketing team, and others at the publishing house that your book is worth taking on. It is well worth your time to get a number of people to help you shape your manuscript before you start submitting to agents. I always tell potential clients that their manuscript needs to be 100% complete as far as they are concerned before they send it to me and then they have to be prepared to be told there is a lot more work to be done.

DF: What do you look for when you're reading a manuscript?

CR: I’m always looking for beautiful language and a distinct voice, but currently I’m desperate for plot. I keep getting my hands on gorgeously written manuscripts that don’t take me anywhere and I have to say no because the books are too quiet. Look at 2015’s big fiction successes: A Little Life, A Brief History of Seven Killings, and Fates and Furies. These books are sweeping and epic and that’s what I’m looking for right now. I love for a novel to take me on a journey. It doesn’t have to be far but I want to keep moving. I have to be compelled to turn the page. I was indoctrinated into novel reading by the works of Morrison and Steinbeck and Tartt and Cunningham, and I’m very sensitive to voice, prose, and plot all working together to propel a story forward. It’s elusive, but it’s out there.

DF: You must read a ton during the day. Are you able to unplug from your professional persona and enjoy reading when you’re off the clock?

CR: Actually, I don’t read all that much during the day because there isn’t time. I hear this from other agents and editors as well and the general consensus, I think, is that we do our reading for work on our own time.

Part of my job as an agent is to know and to understand the current book market, and this means, on top of reading solicited and unsolicited submissions and revisions of manuscripts I am working on with clients, I also have to keep up on current books that are selling. I need to read books that are working and apply that knowledge to projects I’m considering. I have taught myself to call this latter type of reading “pleasure reading” as it doesn’t directly correlate with a specific business project.

And, like any good bibliophile, I keep a list of books, old and new, that I want to read and I am adding to this list constantly. Being an agent means being a book enthusiast and this trait can be a double-edged sword because there is so much I want to read and if I overhear someone talking about a book excitedly, I get so overwhelmed that I’m willing to drop everything and start reading it immediately. I have trained myself to be the type of reader who has many books going at once and right now, other than manuscripts I’m reading for work, I’m reading Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus, Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins, and Paul Elie’s The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage. All of them are blowing my mind, by the way.

To answer your question: for this literary agent, when it comes to reading I am never off the clock, but there are times when I am less on the clock than other times.

DF: Who are some writers you’ve discovered that readers should be aware of?

CR: I’m hesitant to use the word “discover.” If anything, I feel like I’ve been fortunate to have great writers discover me. I’ve never had to talk myself into taking on a novel but I have had to talk writers into letting me take on their novels. Also, for every novel I’ve taken on, I have known from page one that I love the book. No exaggeration. I can’t offer representation based on page one, but in every single case, in hindsight, I’ve known that I love the book based on the first page. That’s what good writing does.

In the case of Belcher’s Lay Down Your Weary Tune, I read the first chapter and had to have my friend Beth Staples, editor for Lookout Books and Ecotone, talk me out of calling him and offering him representation before finishing the novel. The first novel I sold was Jennifer Pashley's The Scamp (Tin House Books) and the first line of the manuscript (it was changed in revision) was “She killed the baby.” Come on!

My favorite story about signing a client is Andrew Hilleman’s. Andy’s manuscript World, Chase Me Down (Penguin, 2017) was 172,000 words and I was loving it! But it was so long that I couldn’t read it fast enough and Andy had a couple of other agents considering the book. I was scared I would lose the novel so I ended up offering him representation before I was halfway through the manuscript. He accepted my offer based on the fact that I had recently sold Taylor Brown’s debut novel. Andy had ordered Taylor’s short story collection in the meantime, loved it, and wanted to be represented by the same agent who represented Taylor. Since then, Taylor has read World, Chase Me Down, given it a fantastic blurb, and raves about it at dinner parties!

I’ve also been fortunate enough to work with fantastic memoirists Gwendolyn Knapp, After a While You Just Get Used to It (Penguin Random House) and Peter Selgin, The Inventors (Hawthorne Books, 2016)

DF: What’s your advice for aspiring writers?

CR: Stop talking about writing and write.

DF: Can you name one random fact about yourself?

CR: As I type this, I’m wearing a sweatshirt that belonged to my maternal grandfather, Alton Nelson. It is blue with yellow lettering and it reads: "It’s hard to be humble when you are Swedish." My good friends, writers Xhenet Aliu and Timothy O’Keefe, suggest I sell the design to Urban Outfitters, collect my millions, and take an early retirement.

To find out more about Christopher Rhodes, visit The Stuart Agency’s official website or follow him on Twitter @CR_agent.

Investigating Crime at the End of the World With Author Ben H. Winters

Ben H. Winters (photo credit: Mallory Talty)

By Daniel Ford

Noir lovers will be familiar with the opening scene of author Ben H. Winters’ award-winning novel The Last Policeman. A body is found hanging in a McDonald’s bathroom and a hardboiled detective smells foul play. His colleagues tell him not to bother tracking down leads because the case looks like a suicide. Detective Hank Palace does it anyway. Seems like typical crime fiction, right?

Well, what I didn’t tell you is that Palace is living in a world that is about to be annihilated by a meteor hurtling toward Earth. He’s one of the last people on the planet still willing to do his job in the face of certain and inevitable doom.

Winters’ novel spawned well-reviewed two sequels that earned praise from the likes of author John Green and Publisher’s Weekly. He talked to me recently about his early influences, writing for different genres, and the inspiration behind The Last Policeman.

Daniel Ford: When did you decide you wanted to be a writer?

Ben H. Winters: I've known it, in one way or another, since I was a kid. It took me a long time to know what kind of writer I wanted to be, or was meant to be, I guess. I was a newspaper columnist, in college; I was standup and an improv comedian; I was a playwright and a lyricist. So a lot of writing, but fiction came late.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

BW: When I was a kid I read a lot of fantasy and science fiction. I read Robert Asprin, I read Heinlein and Asimov. I remember the Wild Card books edited by George RR Martin. (Huh, whatever became of that guy?) I remember being transfixed by Farmer's To Your Scattered Bodies Go, at age 14 or 15. The first "literary" author I really got into was Kurt Vonnegut, and then in college I fell in love with Charles Dickens.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

BW: I always try to outline, and always end up abandoning the outline and then coming back to it and then starting a new one and then abandoning that one too, and it goes on like that until the novel is done. I've stopped being annoyed at myself for not being able to keep to an outline. It will always be impossible to keep to the outline; it will always be valuable to try. I listen to music constantly. I vary it depending on my mood, or the mood of the story. A lot of Dylan, a lot of Tom Waits, a lot of opera. Two days ago I discovered a songwriter named Langhorne Slim and his work is heavily influencing my writing at the moment.

DF: Your bio also says you’ve written extensively for the theater. Does your writing process change at all when you’re writing for other genres?

BW: The main difference in writing for the theater is that it is much more collaborative, earlier on, especially because I mostly wrote writing musicals, which involve not just your imagination, but that of the composer, the director, the choreographer, the actors, and so on. If you can't accommodate your ideas and let them be enlivened and improved by the other artists, you're screwed. Novel writing is by its nature a much more isolated process, which usually I love and sometimes casts me into pits of despair.

DF: Since you’ve also worked as a journalist, I have to ask what you think of the current state of journalism. Also, what’s the most entertaining story you ever worked on?

BW: Smarter people than me will have to opine on the state of journalism. I wrote a piece once where I went with a group called Anti-Racist Action to protest outside the suburban home of a local Neonate asshole. Who emerged from his house to protest the protest, and managed to single me out, correctly identify me, and tell me he "doesn't talk to Jews." That was a pretty exciting story.

DF: What inspired your Last Policeman trilogy?

BW: I have always wanted to write a detective story. Because I was pitching this book to Quirk Books, a publisher that skews toward books with big hooks and big concepts (i.e. Pride and Prejudice and Zombies), I knew I wasn't going to just do your basic police procedural or detective book. I thought a cop solving cases even though the world was going to end was a pretty sharp angle, and that's where I came up with the asteroid.

DF: How much of yourself ended up in Detective Hank Palace? Would you handle a looming apocalypse as well as he does?

BW: I wish I was more like him. I doubt very much that I would have the integrity to keep working, and hang on to my moral sense, as long as he does. The thing is, my job (writer, writing teacher) isn't like being a police officer: nobody relies on it for their immediate safety or well being. I hope I would handle the looming apocalypse by protecting my children as much as I could for as long as I could.

DF: How did you develop the rest of the characters and themes in The Last Policeman? What are some of the things you wanted to explore in this world on the brink of extinction?

BW: Once I had this basic plot idea (cop solving crimes though the world is ending), once I got going on it, the themes presented themselves, really. Oh, I said, this is a book about death. Oh, this is a book about how we order our lives, given the fact that life, for all of us, is bounded. I didn't set out to do a book about those things—I set out to do a cool mystery. I was lucky enough to conceive a plot that suggested those themes, and then I just rode where they took me.

DF: How long did it take you to write The Last Policeman, land an agent, and publish it? Did you know it was going to be a trilogy when you started?

BW: I was in the very fortunate position of having an existing relationship with Quirk Books—I had done a bunch of humorous nonfiction titles for them, and then three somewhat less serious novels: Sense & Sensibility & Sea Monsters, Android Karenina, and Bedbugs. So my editor there, Jason Rekulak, and I had this back and forth, looking for the next thing to do together. I pitched him this idea about the cop and the asteroid, and he said what remains one of my favorite things anyone has ever said to me: "it sounds like it should be a trilogy." So before I really got going on the first one, I knew there would be three, and that helped me get that first book right, knowing I had time in the next two to edge closer to the end of the world.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

BW: The best writing instruction you will get is from reading great writing. Not necessarily in your genre—don't just read mysteries because that's what you write, and not even necessarily fiction. Read poetry; read lyrics; read nonfiction; read the newspaper; read everything. That's how you learn what makes a good sentence, and what makes a good story.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

BW: I was not born with the "H." in my name (Ben H. Winters). My middle name is actually Allen. When I got married, my wife took my last name and I took the initial of her maiden name into mine.

To learn more about Ben H. Winters, visit his official website or like his Facebook page.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

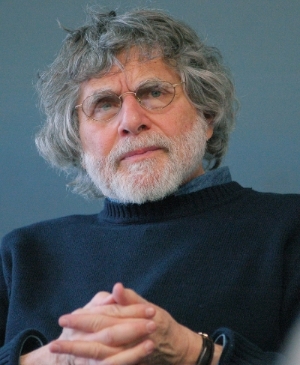

Following Where the Story Leads: A Conversation With Author and NPR Staple Alan Cheuse

Alan Cheuse

By Daniel Ford

You may know Alan Cheuse as a commentator on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered,” however, he’s also an author in his own right!

Throughout his career, Cheuse has published five novels, four collections of short fiction, two volumes of novellas, a memoir, and a collection of travel essays. All that and he has to find time to read all the books he reviews on the show! That’s true dedication to the craft of writing and creativity.

Cheuse’s latest work, Prayers for the Living, was published through Fig Tree Books and is “an epic family saga about the American Dream gone to pieces.” The author’s lyrical prose makes you feel like you’re at the main characters’ kitchen table, listening to this tortured family tale.

Cheuse recently answered my questions about his work with NPR, his writing process, and how he developed Prayers for the Living into a novel.

Daniel Ford: You’ve been reviewing books on “All Things Considered” since 1980. When did you first fall in love with books?

Alan Cheuse: My first encounter with a book and reading was purely visceral. My father, a native Russian speaker read to my when I was very young from a collection of Russian fairy tales, and I can still hear the shush-and-slide his Russian vowels and the clacking of the consonants, and I can still recall the scent of the book (which he had kept stored in an old trunk sent from Shanghai to his first American address somewhere in Brooklyn)—it gave off the odor of oranges under a warm sun. I never learned Russian, but became a devoted reader of sea-stories and fantastic fiction fairly early on in my primary school days. And went on became a science fiction fanatic in middle school and high school. Though I was curious about some of the books on display in the adult section of the Perth Amboy New Jersey library I frequented after school. There was a novel called Invisible Man that I picked up and read for a paragraph or so. And then I found Arthur Clarke’s work. And early in high school I found D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce in a local hole in the wall bookstore on our main street.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

AC: The adventure novels and the science fiction opened my mind to what the imagination might create (though I couldn’t have put that into words back then). But probably James Joyce and Lawrence, and later Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf.

DF: How did your training as a literary scholar help (or perhaps hinder) your first writing projects?

AC: I can only say it helped, because it made it possible for me to get a teaching post where I could devise courses filled with all the reading I needed to do in order to become the writer I am—a cycle of narratives from Gilgamesh and the Homeric epics all the way on through Chaucer and Shakespeare and Cervantes and the great English, Russian, French, and Italian novelists. And modern writers from Gertrude Stein and Sherwood Anderson and Joyce and Hemingway and Faulkner and Woolf and Cather—oh, the long, classic line.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

AC: With a novel I write a draft and revise, draft and revise, and so forth over some years until an editor and my best readers (headed by my wife) say I am getting close. With a story I do the same, though the process is more luxurious, because it only takes a few weeks or a few months to complete a story. But music? No. The only writers I know who listen to music while they compose are poets. Makes me wish I were a poet!

DF: You haven’t tied yourself down to any one genre in your career, writing everything from short stories to novellas. Is that a reflection of your personality or were you just following where your stories led? And do you have a particular favorite genre?