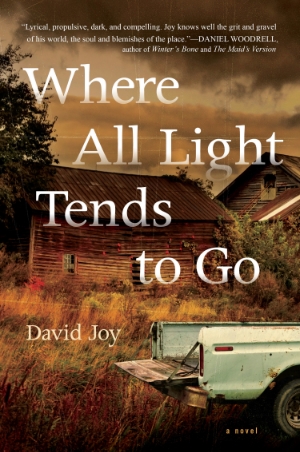

David Joy (Photo credit: Alan Rhew)

By Daniel Ford

There are character studies, and then there are character studies armed with rundown pickup trucks, rotgut bourbon, fermenting single wides, and hillbilly kingpins.

David Joy’s debut novel Where All Light Tends to Go, which is available to purchase starting today, is very much the latter. After reading M.O. Walsh’s My Sunshine Away and watching the recent episodes of the final season of “Justified,” I was primed to thoroughly enjoy Where All Light Tends to Go, an “Appalachian noir” that tells the story of a young man caught at the crossroads between his meth-dealing father and freedom with the love of his life. I’ll have a more extensive review of the book later this month, but I can assure you that you’ll be cheering and crying in equal measure for Jacob McNeely by the end.

Joy was kind enough to answers some of my questions recently about his inspiration for Where All Light Tends to Go, his writing process, and why persistence is so important for aspiring writers.

Photos courtesy of G.P. Putnam's Sons

Daniel Ford: I heard you were on book tour for Where All Light Tends to Go with M.O. Walsh. How much fun did you have promoting your debut novel?

David Joy: I met Neal (M.O. Walsh) in the Charlotte airport on the way to SIBA 2014 and we became really quick friends. We both had debut novels coming out of the same house, we were both Southerners, and we both took our bourbon with ice, and that type of thing leaves little room for arguing. Last fall, me, Neal, Ace Atkins, and C.J. Box went with Putnam for a Books, Beer, and Bourbon Tour hitting Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, and New York City over the course of four days. It was an absolute whirlwind, but it was a lot of fun. I’ll see Neal again in a few weeks in New Orleans for a reading at Octavia Books, but he and I text each other every few days just to see how things are going.

I do think some people have a misconception about something like a book tour. From the outside it seems absolutely wonderful to be traveling around the country and seeing cities and meeting people, but at the same time writers are typically people of solitude. Unlike music or theatre, writing is a lot closer to something like painting where the work is done alone and in a fashion where the art is created without the intention of the artist to ever interact with his/her audience. I typically interact with very few people in my daily life and I rarely, if ever, leave the mountains. That being said, I have fun on the road but it wears me out quickly. It doesn’t take me long to start missing Jackson County.

DF: When did you decide you wanted to be a writer, and how did you develop your voice?

DJ: I grew up in a really rich storytelling tradition, and I think that had a major influence on me early. My parents had an electric typewriter under one of the end tables and some of my earliest memories are dragging that machine out onto the shag carpet. I can remember the way it would heat up the paper and the smell of the paper, the way the letters sounded as they hammered the page. I can’t really remember any of the stories, but my mother says I was doing that before I could spell. She said I’d tell her what I wanted to say and she’d dictate the keys to press to spell the words. So I think really early on, like five or six years old, I don’t know that I consciously knew that I wanted to be writer, but I think I was fascinated with what a word could do on a page. I wrote my whole life, but I started to take it seriously and know that I wanted to make it a career when I was in high school, and then especially once I got into college. I started young, but none of that early work was any good. I don’t think I wrote anything worth a damn until my mid-twenties and even then it wasn’t what it is now. I’m not a very quick study.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

DJ: The earliest novels I remember having a real impact on me were Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet and Walter Dean Myers’ Fallen Angels. I was a really weird kid. I remember checking out Shakespeare’s Hamlet from the library when I was either in elementary school or sixth grade. I read that and I read Nostradamus. My dad was obsessed with Stephen King when I was little, and I tried to read a few of those. Of course I didn’t understand any of it. I don’t really know what I was doing, but I remember having a fascination with the language of it and the way it sounded when I read it aloud. But as far as the major influences for what I’m doing now, I’d say Larry Brown, Daniel Woodrell, William Gay, Cormac McCarthy, Ron Rash, Harry Crews, Faulkner, O’Connor, just the usual suspects for someone who grew up in the South and writes the types of things I write.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

DJ: A lot of times I’ll have a song that I’ll attach to a character or a story, so for Where All Light Tends To Go, Jacob’s song was Townes Van Zandt’s “Rex’s Blues.” But I never play the song while I’m writing. I have to have complete silence while I’m working, and I typically seem to be at my best in the hours between midnight and sunrise when the whole world has stilled. As for the song, though, it’s something I’ll usually play at the start, similar to how you’d build the sound of a singing bowl as you’re headed into meditation. I’ll use that song as a way to enter the story, but once I’m inside I need silence.

I never outline. My work is character driven. I have characters that develop very clearly. I can see everything about them, from the way they look to the type of coffee they buy. Once I have a character like that it’s just a matter of throwing him into a situation and seeing what he does. As far as the daily writing habits, I usually have a line that’ll come to me and that will start it off. Sometimes I wake up with that line in my head, or sometimes it might take a while to find it. I’m very methodical. I need one good sentence before I can move forward. Sometimes I might sit all day without anything. I’m not one for writing just for the sake of writing. I trust that it will come and if it’s a matter of waiting around then I’ll wait.

DF: Where did the idea for Where All Light Tends to Go originate? Was it something you’d been thinking about for a long time, or did it come to you like a bolt of literary lightning?

DJ: I lived with an image of Jacob for a long time before I heard him. I was at a friend’s hog lot and we were talking and I remember having this image of a very young boy standing over a hog he’d just killed and realizing how much power he had over life and death, a very big idea for a child. That image haunted me for a long time and I kept trying to write his story but I kept getting it wrong. I burned about 40,000 words of a draft the second time around and started from scratch. Then I woke up in the middle of the night one night and I could hear him. I could hear his story clear as day just like he was talking to me. Once that happened it was just a matter of keeping up. So it was kind of a mix of what you’re asking in that I lived with the image for a very long time, but when the story finally came I was cooking with gas.

DF: I love that your book is referred to as “Appalachian noir.” What does that term mean to you?

DJ: When I described that novel as Appalachian noir, I was adapting a term Daniel Woodrell had used to describe his novel Give Us A Kiss, which at the time he called country noir. I think Appalachia has a style that in a lot of ways is uniquely its own. There are similarities to the rest of Southern literature, but there’s a history here that is different. The landscape is different. The people view the world differently. So it was about adapting that term to fit what I was doing. At the same time, Daniel eventually came to distance himself from that term noir, and I think that’s because it has some very specific qualities that he didn’t see his work strictly adhering to. The more I interact with people who are working in that genre the more I realize that our influences aren’t always the same.

Something that’s interesting to me in these discussions, though, is that when you start mentioning people like William Gay or Larry Brown or Ron Rash, there is a general consensus that their work can be classified as noir. If you can classify those writers in that vein then you’d certainly classify McCarthy there and then you could go back to his influences, people like Faulkner or O’Connor, and classify them as noir as well. The reality is that I don’t think any of those writers were doing that intentionally. There seems to just be a lot of similarities between the grit lit that has come out of the South for so long and what has become popularized as noir currently. I don’t have a problem with classifying my work under that title, but I do think I’m rooted somewhere a bit differently. Regardless, these are the types of stories I like and the types of stories I tell, dark, often hopeless stories of working class people doing the best they can with the circumstances they’re given. If someone says something is country noir or Appalachian noir or rural noir, I’ll probably dig hell out of it.

DF: How much of yourself, and family, friends, etc., did you put into your main characters, themes, and settings?

DJ: I didn’t intentionally put any of myself in the book, but as I read back through that novel down the road I started to recognize that there are some similarities between how Jacob and I view the world. I think both of us are extremely skeptical and unwilling to put our faith in others. I think both of us are hesitant to hope for fear of things falling apart. Other than that, very little of myself or my family made it into the novel. I will say that some of the circumstances that Jacob is facing are things I witnessed around me growing up. These weren’t circumstances I personally faced, as I grew up privileged in a lot of ways. I wasn’t privileged as far as money, but I grew up in a household where my parents loved me and that’s more than I can say for a lot of the people I grew up around. A lot of the kids I grew up with were surrounded by drugs and violence very early and when you’re coming out of poverty these things tend to be glorified. That reality is something that I’m very familiar with because of where I grew up. I never had a life like Jacob’s, but I know plenty who were pretty damn close.

As for the setting, the novel is set very specifically in the county where I live. Most of the places in the novel exist. You could come here and eat at the restaurant where Maggie and Jacob have dinner. You could ride up Highway 107 and see the bouquets of flowers lining the ditch below Hamburg cemetery. You could hike in and sit at the Little Green overlook in Panthertown. I did this because I’ve just never seen the sense in creating some place and creating a name for that place only for it to be a blurred recreation of something that actually exists. I just prefer to use the landscape I know.

DF: How do you balance writing and marketing your work (i.e. book tours, engaging w readers on social media, etc.)?

DJ: Not very well, honestly. I’ve never been a very social person so the exposure is one of the hardest things for me to get over. I live in a place where you wave at folks on your drive into work in the morning and wave at the same folks as you pass on the way home that evening. The only things big around here are the mountains. So to open a magazine like Cosmopolitan or a paper like The New York Times knowing that they mention me is a tad overwhelming. The only way I can describe how it feels is like walking into a room where something really important is going on, church or a funeral or a business meeting, and everyone in the room turning to stare at you. That deer-in-headlights kind of feeling is something I’ll never get used to. But as far as balancing the marketing and the work, I try to just keep my head down and put in the hours. I’m at my happiest when I’m inside of a story. I get genuinely excited, like stand up and shadow box excited, when I get a sentence just right. The music of language is the most beautiful thing I know. When you get that type of enjoyment out of something, it’s hard when you have to do other things. At the same time, the marketing is extremely important, I’m working with a whole team of wonderful people, I get to meet some beautiful souls, and it’ll all be over before I know it. Life’s too short not to experience every emotion there is. So I count myself awfully lucky.

DF: Now that you have your first novel under your belt, what’s next?

DJ: I have a second novel finished that’ll be coming out with Putnam some time next year. We’re still playing around with a title, and there’s still a lot of work to be done in the revisions, but the manuscript is finished. As far as what happens in the book, the trigger for the narrative is that there are these two best friends, Aiden McCall and Thad Broom, who go to buy drugs and wind up witnessing the accidental suicide of their drug dealer. All of a sudden you’ve got these two addicts with piles of drugs and money dropped in their laps. But as far as what the book’s about, it really became a story about trauma. It’s about how the things we carry through our lives come to govern the choices we make. I’m really happy with it and I’m looking forward to what my editor and I can do to shape it into something big. As far as after that, I’ve got something new I’m working on. I don’t seem to be able to go very long without some character finding his way inside my head.

DF: What advice would you give to up-and-coming writers?

DJ: Persistence. That’s it. That’s the difference between people who make it and people who don’t. I wrote for a very, very long time before I ever got to anything close to something publishable. Some of the earliest writing I had was on notebook paper and I kept it in shoeboxes, and my mother called one day to see what I wanted to do with it. There was probably a thousand pages and I told her to take all of it out into the yard and set it on fire in the burn barrel. A lot of people can’t understand that, but it was the fact that I knew the writing wasn’t any good. It was important. I had to get it out of me. But once it was out, there was no other use for it. I’m probably well into 2,000 pages now and I’m still not anything close to what I would consider good. Whereas that might seem futile to some, it’s that futility that makes it so beautiful. It’s knowing that I’ll do this the rest of my life and never get it just right that makes it worthwhile. You know, Faulkner said if the artist were ever able to get it perfect, “nothing would remain but to cut his throat, jump off the other side of that pinnacle of perfection into suicide,” and I think that’s true. There just wouldn’t be anything else to do with your life.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

DJ: If you’ve ever seen how a monkey holds onto something, that’s how I hold a pen or pencil, absolutely simian. When I sign my name, for instance, the pen or pencil is clenched in my fist. I catch hell everywhere I go about it. People think I’m some sort of freak or something.

To learn more about David Joy, check out his official website, like his Facebook page, or follow him on Twitter @DavidJoy_Author.